Introduction

Political transitions represent some of the most delicate moments in the life of a state. Whether facilitated by caretaker governments, interim regimes, or structured party handovers, these transitions determine not only the stability of electoral outcomes but also the resilience of democratic institutions. Scholars of comparative politics argue that the effectiveness of such transitions lies in their ability to balance legitimacy, neutrality, and constitutional adherence (Ahmed, 2011). The historical experiences of Bangladesh, alongside comparative cases such as Pakistan and Australia, provide valuable lessons for designing institutional arrangements that sustain democracy during transitional periods.

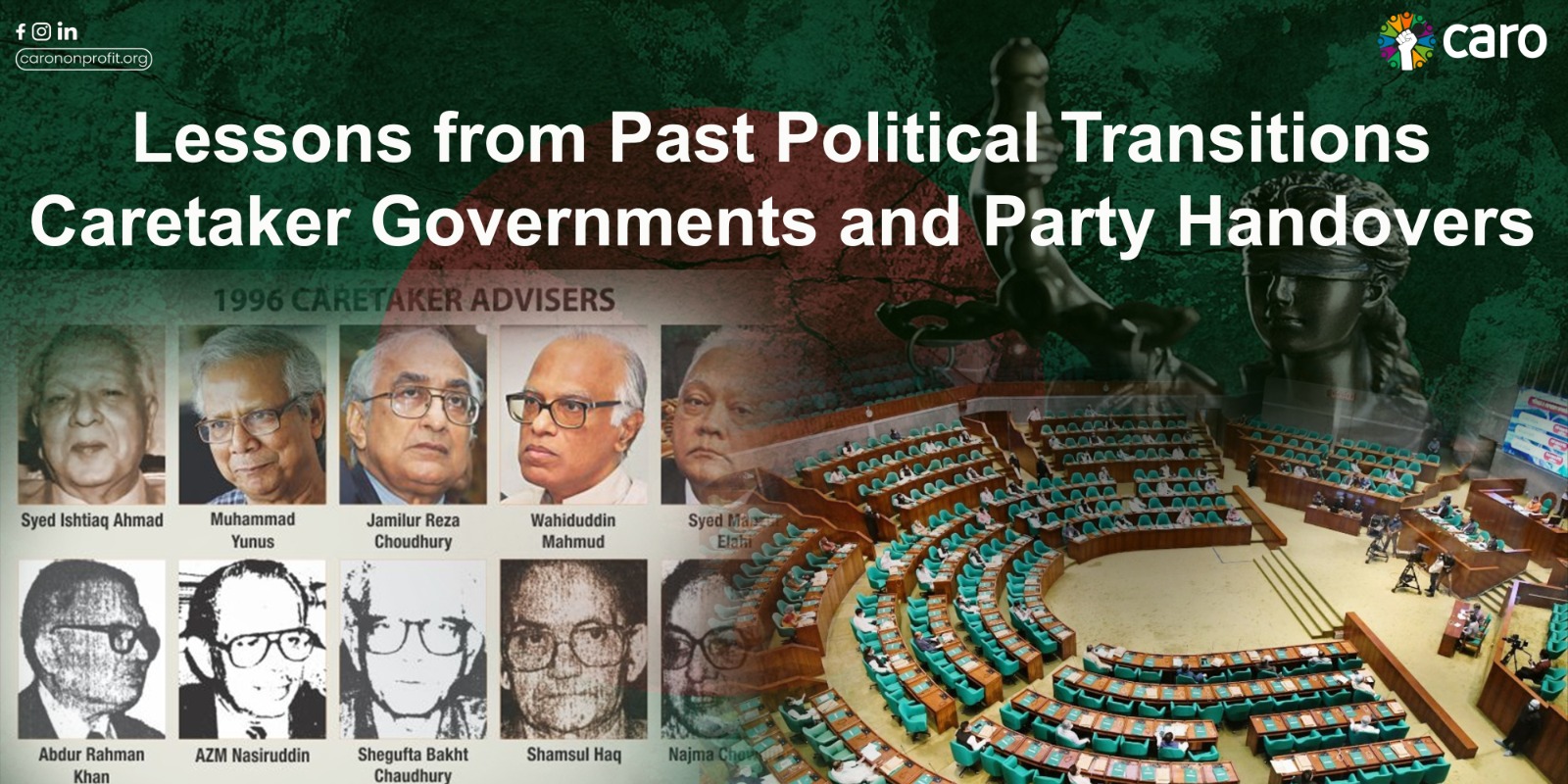

The Bangladeshi Experience

Bangladesh has been at the center of debates surrounding caretaker governance. The introduction of the Non-Party Caretaker Government (NPCG) system through the 13th Amendment (1996) marked an attempt to depoliticize election management and restore trust in electoral outcomes.

- 1991 Transition: Following the fall of military rule, the transition to parliamentary democracy was facilitated through interim arrangements, creating a precedent for neutral oversight (Islam, 2013).

- 1996 and 2001 Elections: These elections, supervised by caretaker governments, are widely regarded as comparatively free and competitive, demonstrating the credibility of neutral administration.

- 2006–2008 Crisis: Disputes over the neutrality of the caretaker system escalated into political violence and ultimately led to an extended interim regime backed by the military. While this administration implemented institutional reforms such as updating voter rolls, it also overstepped its mandate, raising questions about democratic legitimacy.

- Abolition in 2011: Through the 15th Amendment, the NPCG system was abolished, leaving electoral processes fully under the control of incumbent governments. Subsequent elections (2014, 2018) have been marred by controversy, opposition boycotts, and allegations of manipulation (Ahmed, 2011).

This trajectory illustrates both the strengths and the fragilities of caretaker arrangements: while they can enhance electoral trust, they also risk overextension, politicization, or capture by extra-constitutional forces.

Comparative Perspectives

Other states’ experiences reinforce these lessons. In Pakistan, caretaker governments are constitutionally mandated before elections, though controversies persist regarding neutrality and military influence (Rizvi, 2017). By contrast, Australia relies on strong democratic conventions: caretaker governments function with limited authority, refraining from long-term policy decisions, and their legitimacy rests upon political culture and institutional trust (Weller, 2010). These examples underscore the importance of both formal legal frameworks and informal political norms in shaping successful transitions.

Key Lessons from Past Transitions

- Neutrality as Legitimacy

Neutral caretaker administrations strengthen the credibility of elections. Perceptions of partisanship, however, delegitimize transitions and provoke crisis. - Mandate Limitation

Transitional governments should exercise minimalist authority—restricted to managing elections and routine governance. Expanded reform agendas, as in Bangladesh (2007–2008), risk accusations of overreach. - Time-Bound Mechanisms

Fixed constitutional timelines are essential. Extended interim periods generate uncertainty and open avenues for authoritarian entrenchment. - Constitutional Clarity

Caretaker frameworks must be clearly enshrined in law, including criteria for appointment, scope of authority, and mechanisms of accountability. Ambiguities invite manipulation. - Public Trust and Inclusivity

The legitimacy of transitions is grounded in public perception. Transparent electoral management, consultation with opposition parties, and observer participation strengthen confidence. - Guarding Against External Capture

Military or external interference undermines the democratic function of caretaker systems. Domestic consensus and constitutional safeguards are critical to prevent undue influence.

Implications of Abolishing Caretaker Systems

The removal of caretaker provisions without consensus risks destabilizing the democratic process. Bangladesh’s post-2011 experience highlights:

- Erosion of trust in electoral management, particularly among opposition parties.

- Increased risk of boycotts and extra-parliamentary confrontations.

- Diminished legitimacy of electoral outcomes, both domestically and internationally.

This suggests that even if the caretaker model is flawed, its absence without alternative mechanisms of credible oversight can intensify democratic crises.

Conclusion

Past experiences with caretaker governments and transitional arrangements demonstrate that political transitions are moments of both opportunity and vulnerability. When designed with constitutional clarity, limited mandates, and broad political acceptance, caretaker regimes can restore trust in polarized environments. Conversely, when manipulated, extended, or abolished without consensus, they deepen political instability.

Bangladesh’s trajectory serves as both a cautionary tale and a source of insight for states grappling with similar dilemmas. Ultimately, the key lesson is that the legitimacy of democratic transitions rests less on the presence or absence of caretaker governments alone, and more on the normative culture of trust, transparency, and constitutionalism that underpins them.

References

- Ahmed, Nizam. (2011). Abolition or Reform? Non-party Caretaker System and Government Succession in Bangladesh. The Round Table: Commonwealth Journal of International Affairs, 100(414), 269-283.

- Datta, Sreeradha. (2009). Caretaking Democracy: Political Process in Bangladesh, 2006–08. New Delhi: Institute for Defence Studies and Analyses.

- Islam, Md. Nazrul. (2013). Non-Party Caretaker Government in Bangladesh (1991-2001): Dilemma for Democracy? Developing Country Studies, 3(2), 1-9.

- Rizvi, Hasan Askari. (2017). The Military and Politics in Pakistan: 1947–1997. Sang-e-Meel Publications.